At its core, Richard Höglund’s art addresses that most long-standing of artistic concerns: what painting is, and what it means to paint. In particular, his practice, which centres around drawing and painting, critiques those traditional media by using and transmuting their fundamental material processes. For Höglund, painting is a ‘bare bones’ act, a simple and historic one, a fundamental human activity. With this conception, Höglund extends his investigation on the nature of painting into an exploration of what it is to be human. His overarching concern becomes how we articulate the world around us through the material cultures of art and architecture, and the intellectual cultures of language and philosophy. Synthesising ideas from these fields, it is only after a long process of research and contemplation that Höglund develops each series of paintings.

The paintings presented here are from Höglund’s most recent series, the Four Quartets, and are characteristically dense with material and philosophical references. Their pared-back, simplified aesthetic draws on the geometric principles of ancient Egyptian architecture, as well as those of Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. Their chiaroscuro comes from Dutch master Rembrandt and American abstractionist Ad Reinhardt, both of whom were celebrated for creating luminosity out of darkness. The series title is taken from American-British writer T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, four poems published in the 1940s on the theme of man’s relationship with time, the universe and the divine. Eliot was himself inspired by Beethoven’s late string quartets.

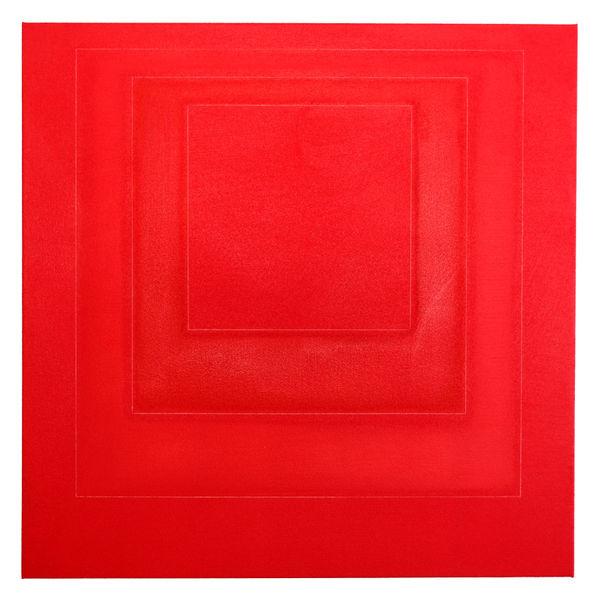

The most direct reference these paintings make is to the iconic Homage to the Square series by German-American artist and educator, Josef Albers. Starting in 1950 at the age of 62, Albers developed the series until his death in 1976, creating hundreds of variations. Each of his compositions features the basic components of three or four squares set inside one another in a manner that is concentric but weighted toward the bottom edge. In Höglund’s own homage, the three or four nested squares appear to resist gravity, hovering at the top of the canvas – a further subtle reference to Russian painter Kasimir Marevich’s 1915 ‘Black Square’ icon – and accentuating the transcendental quality of each painting.

Materially, Höglund’s paintings are intricate and allegorical. First outlining his squares in gold- or silverpoint, Höglund creates a framework into which dark pigments like raw indigo are pressed into a prepared ground. At first sight the paintings appear black, yet as one moves around each individual square emerges, defining itself by the way light is absorbed or reflected by the surface. These optical effects are created through Höglund’s sophisticated use of ground marble and basalt, as well as pulverised bone, in the first layer of the painting. Selected for how they reflect light, these materials also have symbolic meaning for the artist: “I think of indigo as the deep, whether the cosmos or the sea. I think of bone dust as the eventuality of the body, and marble dust as the eventuality of what we make. Basalt is my rock of the North and is reminiscent of voyages I would undertake in a mad hunt for a lost Burkean sublime.” In some instances, indigo is combined with copper or iron to create an iridescence that causes the squares to glow, hovering ahead of the painting surface. Where Albers explored the interaction of colour in his paintings, Höglund pursues a study of light itself: “These paintings come alive in low, natural light as it changes by the hour and the season. They are perhaps at their best at dawn, or at twilight, when the eye needs time to adjust. A painting is not an image. A painting requires your presence, light and time; time for looking and for apparitions to come and go with your thoughts.”

- Text by Louise Malcolm

The paintings presented here are from Höglund’s most recent series, the Four Quartets, and are characteristically dense with material and philosophical references. Their pared-back, simplified aesthetic draws on the geometric principles of ancient Egyptian architecture, as well as those of Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. Their chiaroscuro comes from Dutch master Rembrandt and American abstractionist Ad Reinhardt, both of whom were celebrated for creating luminosity out of darkness. The series title is taken from American-British writer T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, four poems published in the 1940s on the theme of man’s relationship with time, the universe and the divine. Eliot was himself inspired by Beethoven’s late string quartets.

The most direct reference these paintings make is to the iconic Homage to the Square series by German-American artist and educator, Josef Albers. Starting in 1950 at the age of 62, Albers developed the series until his death in 1976, creating hundreds of variations. Each of his compositions features the basic components of three or four squares set inside one another in a manner that is concentric but weighted toward the bottom edge. In Höglund’s own homage, the three or four nested squares appear to resist gravity, hovering at the top of the canvas – a further subtle reference to Russian painter Kasimir Marevich’s 1915 ‘Black Square’ icon – and accentuating the transcendental quality of each painting.

Materially, Höglund’s paintings are intricate and allegorical. First outlining his squares in gold- or silverpoint, Höglund creates a framework into which dark pigments like raw indigo are pressed into a prepared ground. At first sight the paintings appear black, yet as one moves around each individual square emerges, defining itself by the way light is absorbed or reflected by the surface. These optical effects are created through Höglund’s sophisticated use of ground marble and basalt, as well as pulverised bone, in the first layer of the painting. Selected for how they reflect light, these materials also have symbolic meaning for the artist: “I think of indigo as the deep, whether the cosmos or the sea. I think of bone dust as the eventuality of the body, and marble dust as the eventuality of what we make. Basalt is my rock of the North and is reminiscent of voyages I would undertake in a mad hunt for a lost Burkean sublime.” In some instances, indigo is combined with copper or iron to create an iridescence that causes the squares to glow, hovering ahead of the painting surface. Where Albers explored the interaction of colour in his paintings, Höglund pursues a study of light itself: “These paintings come alive in low, natural light as it changes by the hour and the season. They are perhaps at their best at dawn, or at twilight, when the eye needs time to adjust. A painting is not an image. A painting requires your presence, light and time; time for looking and for apparitions to come and go with your thoughts.”

- Text by Louise Malcolm

-

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage IX: Air), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage IX: Air), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage VII: Air), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage VII: Air), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage VIII: Air), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage VIII: Air), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage X: Air), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage X: Air), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XI: Terre), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XI: Terre), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XII: Terre), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XII: Terre), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XIII: Terre), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XIII: Terre), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XIV: Terre), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XIV: Terre), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XIX: Feu), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XIX: Feu), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XV: Eau), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XV: Eau), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XVI: Eau), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XVI: Eau), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XVII: Eau), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XVII: Eau), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XVIII: Eau), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XVIII: Eau), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XX: Feu), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XX: Feu), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XXI: Feu), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XXI: Feu), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XXII: Feu), 2022

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets I (Homage XXII: Feu), 2022 -

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets (Homage LXXIV : 17), 2021

Richard Höglund, Four Quartets (Homage LXXIV : 17), 2021